The

Absurdity of the “Dark is Beautiful” Campaign

I

In the Vijay starrer blockbuster

Gilli, the hero’s teenage sister

comes back home dark and sweating after a failed search mission of Aiswarya Rai

and Sachin Tendulkar in the hot sun. Her mother asks her: “Nee ennadi enginukku

kari alli potava maari vanthuirukka?” (Why do you look like one who has been

feeding coal to the rail engine?)

In a much recent horror

movie Kanchana, the hero falls in

love with the sister of his highly Brahminical accented Tamil speaking

sister-in-law. As the hero tells his sister-in-law of his liking to her sister,

she tells him, “Ava unna vida colour da” (She is fairer than you.)

II

In the past few weeks

like many others in this country, I too got emails asking me to sign a campaign

against Emami India and Sharukh Khan. A visit to the campaign page in Facebook told

a lot about the ideas associated with dark skin and the motivations of the

group.

In an interview Nandita Das, the celebrity

campaigner says, “Do you mean to say that there are no dark colored upper class

women?... Especially in mainstream you have to have woman who is fair” (www.desiyup.com

).

And this is precisely

why I think the “Dark is Beautiful” campaign is absurd. Most of the entries in

the fan page underscored that they have been ostracized for being dark; that

they have to work extra hard to prove their worth. And most significantly the

campaigners belonged to elite urban backgrounds.

While Nandita Das is

campaigning for the acceptance of dark skinned individuals, she is talking

within the limitations of an uppercaste/class highly successful woman who was

looked upon as dark and dusky despite her beauty and talent. In the same interview she says that dark

should be looked upon as beautiful and not an exception. The inherent flaw in

the campaign is the glossing over of discrimination based on caste, class,

region, and race as one associated with skin tone.

Take the case of Arpit Jacob for example. Arpit, a

native of Kerala, recounts his experience of studying in a school in North

India. In the school he was called Kalia (black) and haspi (negro). Because of

the ridicule he suffered, he says he joined a college in south India “where

there were more dark skinned people.” It is true that Arpit has been the butt

of ridicule in school for his skin color. But the real reason for being

ridiculed is the fact that he is a southerner and his skin color is different

from his northern class mates. It is no wonder that he felt comfortable in a

college in south India with like skinned people. Unfortunately in the article,

Arpit goes on to generalize on the effects of focusing on negativities in life

(darkisbeautiful.blogspot.in

).

Diya Paul, a communication professional recounts her

trauma of enduring her paternal grandparents’ mournful “ivvelevu karuppa porenthutaa (she

has been born so black!)” and her father’s anguished surprise that his daughter

is black despite a “fair like a foreign import or a North Indian” mother. Added

to this was the general disbelief in her circle that she could not have born

out of her biological mother. She says she even went on to ask her mother if

she was adopted or was there a goof-up of babies in the hospital (www.weekendleader.com/

www.Facebook.com/darkisbeautiful). While it is clear that the

author’s family and her circle are fair skinned people, we need to ask who the

dark skinned ones are.

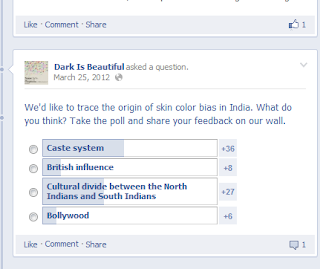

In the “Dark

is Beautiful” fan page in Facebook, there is a vote to trace the origin of skin

color bias in India. Out of the four choices – caste system, British influence,

Cultural divide between the North Indians and South Indians, and Bollywood –

caste system has earned 36+ votes followed by cultural divide between North

Indians and South Indians with 27+ votes. Compared to this colonial influence

and tinseldom had earned only a negligible 6 and 8 vote. While the campaigners have indeed realized

the factors originating skin color bias and the followers have made it quite

evident through their votes, the campaigners have camouflaged caste and

regional bias as superficial a bias as skin color.

The Emami Fair and Handsome advertisement sought to

be withdrawn is viewed as spreading the message that one need not work hard

when their skin is fair. Well, the truth of the argument is beyond question. But

the difference is why is dark skinned detested? Why are dark skinned people

looked down upon? Hira Shah, professor of South Asian Studies, York University

points out the power and authority associated with the rulers in a colonial set

up and the evil doers as dark skinned in many of the Hindu scriptures (http://vimeo.com/16210769

). In the African- American context, colorism had its origin in the

condescending treatment enjoyed by children born out of “slaves and their white

masters” (abcnews.go.com

) who naturally had lighter skin. The bottom line of Professor Hira’s analysis

is that fairer skin means power, authority, and goodness. In the

African-American context it means privilege. Darker skin means the opposite.

The role of media, tinseldom in perpetuating the

fair-successful-beautiful-good equation is beyond doubt. On answering the charges of why Fair and

Handsome and why Sharukh Khan, Kavitha Emmanuel – founder Woman of Worth - says

that they have to start somewhere (darkisbeautiful.blogspot.in ). She also says that “This is not an attack on brands or brand ambassadors, but on

the toxic belief that only fair skin is beautiful" (www.Facebook.com/darkisbeautiful

). And

for this reason alone the credibility of the “Dark is Beautiful” campaign as

people’s movement is shaky. If the campaigners do not want to rub on the rough

side of powerful people, whose conscience are they trying to awaken? How will brands sell

fairness creams without putting forth the idea that fair is better?

In the Indian caste based structural hierarchical

society, is it not a fact that the lower you went the darker was the skin? Is

it not a fact that people in the south are darker than their northern

inhabitants? If you accept dark as beautiful, does it mean that there won’t be

discrimination based on these categories?

The hatred for dark skin tone arises out of a sense

of shame to resemble someone who you would look down upon and vice versa. The

campaigners without addressing the associations of the dark skin are merely

saying, “Look we have dark skin, but we are not like them.”

Nandita Das while acknowledging the presence of

caste and culture behind the obsession with fair skin thinks that “current

causes should be targeted first.” I cannot restrain from asking, when is the

right time to talk about caste and culture based color discrimination? It is

naïve to assume that caste and culture based bias will be forgotten if dark

skin is accepted as beautiful. It won’t be an exaggeration if I say even if the

dark skin is accepted as beautiful the question “whose dark skin?” will still

remain unanswered.

At the very minimum the campaign does not point out

that those who discriminate on skin color are showcasing caste and regional

superiority attitude. Without pointing out the reason I am not sure what the

campaigners aim to achieve. The campaigners never said, “See, you are being

casteist in the guise of color, you are being racist and so on.” Until there is

discrimination based on caste, class, region, and race there will be

discrimination based on skin color. Even thousands of “Dark is Beautiful” campaigns

will not eradicate it.

A campaign which willfully disengages with social

realities is only an elitist movement which need not be taken seriously. Unfairly,

the Bollywood glam-quotient has earned the campaign undue attention from world

over. At its present form the “Dark is Beautiful” campaign is usurping the

voices of those dark skinned people who have lesser means of overcoming the

bias to prove their talent. As Anjali Rajoria says, the campaign is one that of

“highly successful upper caste women who are protesting the loss of few more

lucrative mainstream opportunities due to their relatively darker skin tones” (http://www.dalitweb.org/?p=2039

)

References: